Unravelling the Threads of Anxiety: A Journey Through the Anxious Brain

Oct 14, 2024

As a counsellor, and life coach, my mission is to equip individuals with the knowledge and tools to understand and manage their anxiety. Anxiety, while a universal human experience, can feel isolating and debilitating. By understanding its biological underpinnings, we can begin to demystify its power and develop effective coping mechanisms. This article embarks on a journey through the anxious brain, exploring the neural pathways, brain structures, and neurochemicals that contribute to the development and persistence of anxiety.

The Cortex and Amygdala: A Tale of Two Pathways

The human brain is an incredibly complex organ, a network of billions of neurons constantly firing and communicating with each other. This intricate web of activity gives rise to our thoughts, emotions, behaviours, and our experience of the world. When it comes to anxiety, two key pathways in the brain take centre stage: the cortex pathway and the amygdala pathway [1-3].

Imagine these pathways as two roads, each leading to the destination of anxiety, but through very different terrains [2]. The cortex pathway is a more scenic route, winding through the realm of conscious thought, interpretation, and imagination [3]. It's the road we travel when we overthink, ruminate, and catastrophize. The amygdala pathway, on the other hand, is a shortcut, a fast track designed for immediate action [2, 4]. This is the road our brain takes when it perceives immediate danger, triggering the fight-or-flight response.

The Thought-Fuelled Road: Navigating the Cortex Pathway

The cortex, the outermost layer of the brain, is often referred to as the "thinking brain" [1, 3]. It is responsible for higher-level cognitive functions such as language, reasoning, decision-making, and planning. However, this remarkable capacity for thought can also become a breeding ground for anxiety [3].

The cortex pathway to anxiety typically involves the interpretation of situations as threatening, even when no real danger exists [3, 5]. It's like wearing a pair of glasses that distort our perception, causing us to see threats lurking around every corner. This distorted perception then activates the amygdala, triggering a cascade of anxious thoughts, feelings, and behaviours [3, 5].

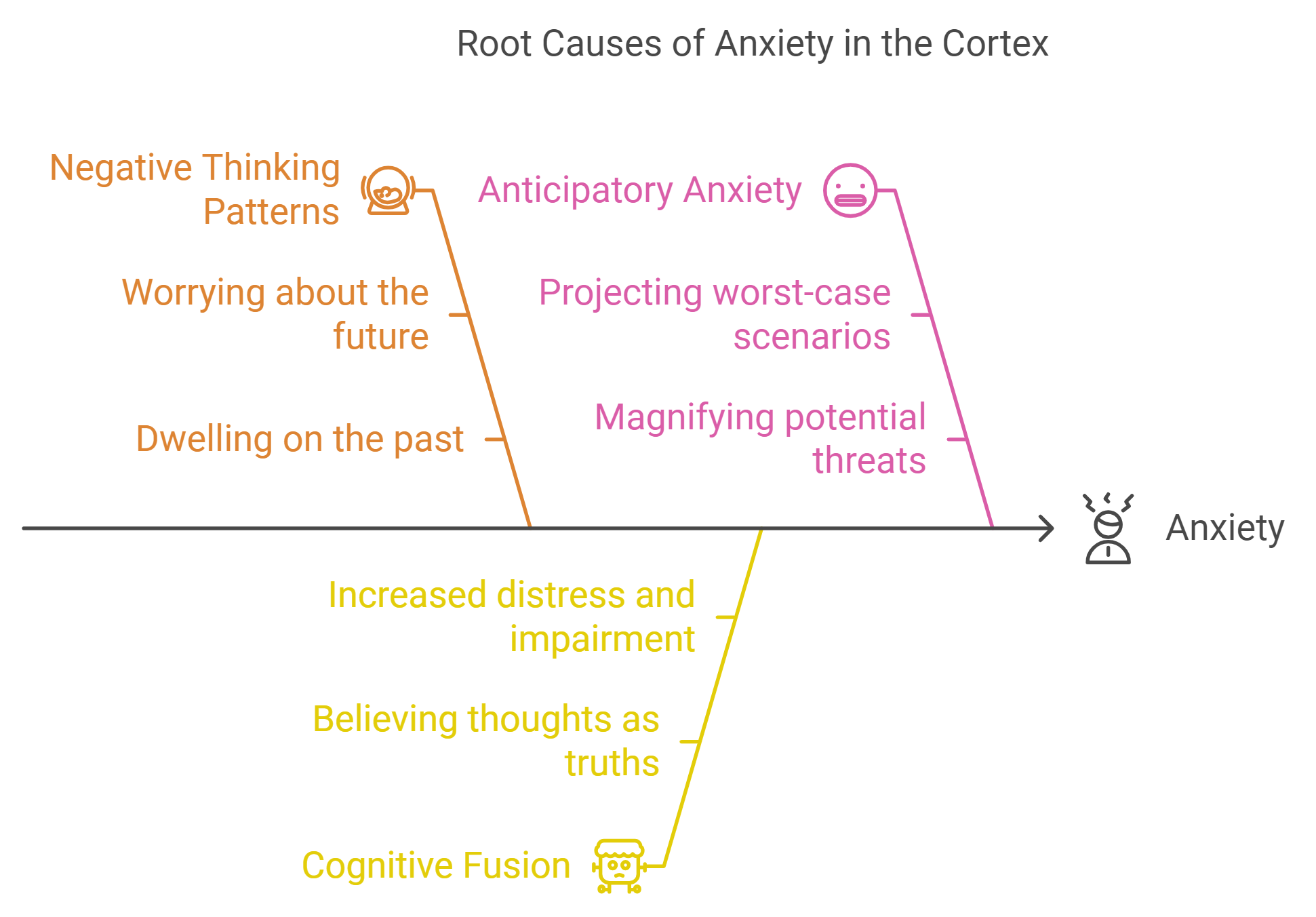

Here are some of the ways the cortex can contribute to anxiety:

-

Negative Thinking Patterns: Our thoughts have incredible power over our emotions. Repetitive negative thoughts, such as worrying about the future, dwelling on the past, or catastrophizing potential outcomes, can fuel anxiety [6-8]. The cortex can get trapped in these negative thought loops, generating persistent feelings of unease and apprehension [6, 8]. Imagine a hamster on a wheel, running and running but getting nowhere. That's what it's like when our thoughts get stuck in a negative loop.

-

Cognitive Fusion: Have you ever noticed how easy it is to become entangled in our thoughts, to believe them without question? This process, known as cognitive fusion, is a hallmark of anxiety [5]. When we fuse with anxious thoughts, we experience them as absolute truths, leading to increased distress and impairment [5, 9]. It's like mistaking a shadow for a monster, our fear becoming amplified by our misinterpretation.

-

Anticipatory Anxiety: The human ability to envision the future is both a blessing and a curse. While it allows us to plan and dream, it can also lead to anticipatory anxiety, the dreadful feeling of worry and dread that often precedes a feared event [5]. The cortex can project itself into the future, imagining worst-case scenarios and generating anticipatory anxiety even before the feared event occurs [5]. It's like living in a perpetual state of "what if," our minds racing ahead to anticipate and magnify potential threats.

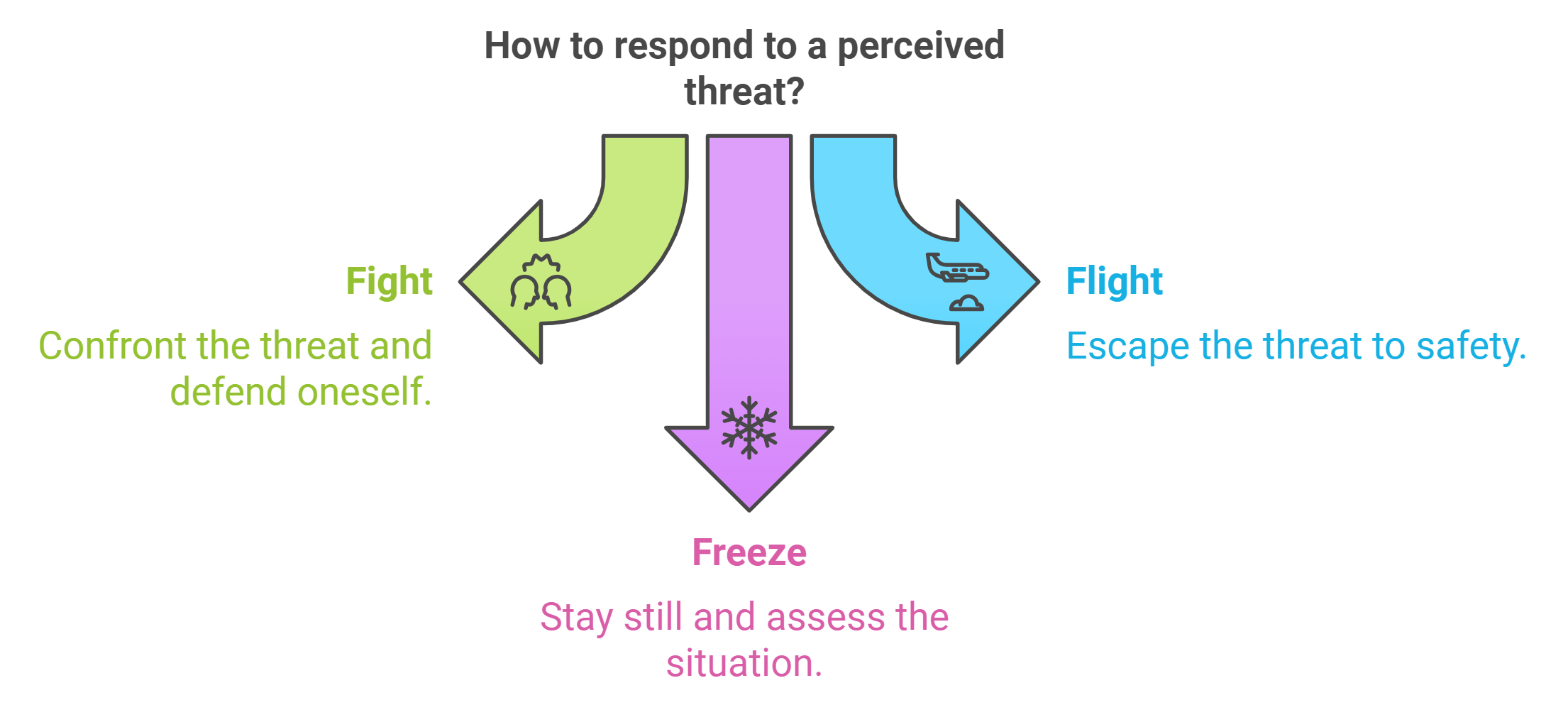

The Amygdala's Alarm: The Fast Track to Fight, Flight, or Freeze

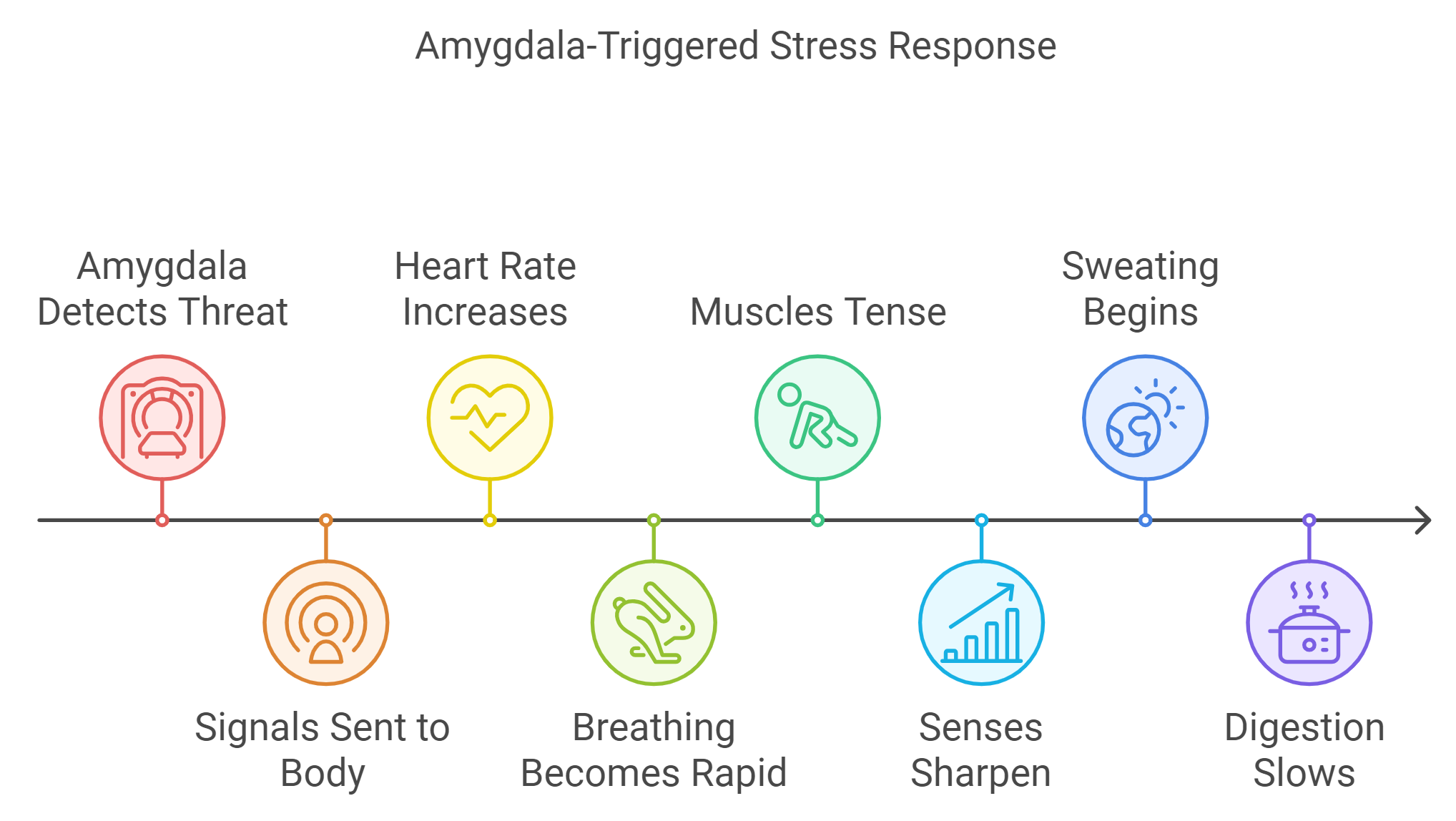

Deep within the brain lies the amygdala, a small, almond-shaped structure that acts as the brain's security system, constantly scanning our environment for potential threats [1, 3, 4, 10]. When the amygdala detects danger, it triggers a rapid cascade of physiological responses designed to prepare us for fight, flight, or freeze [4, 10, 11]. This response, known as the stress response or the fight-or-flight response, is an evolutionary masterpiece, ensuring our survival in the face of danger [1, 4, 10].

Imagine you're walking through a forest and suddenly encounter a bear. Your amygdala springs into action, sending signals to your body to prepare for a life-or-death situation. Your heart races, your breath quickens, your muscles tense, and your senses sharpen. This is your body's way of giving you the best possible chance of survival.

The stress response involves:

-

Increased heart rate and blood pressure: This pumps blood to major muscle groups, providing the energy needed to fight or flee [10].

-

Rapid breathing: Increased oxygen intake fuels the muscles, further enhancing our ability to respond to the threat [10].

-

Muscle tension: Muscles prepare for action, poised to fight or flee at a moment's notice [10].

-

Sweating: Our bodies cool down in preparation for physical exertion [10].

-

Digestive changes: Digestion slows down as energy is diverted to more immediate survival needs, such as fuelling the muscles and brain [10].

While the amygdala's threat detection system is essential for survival, it can sometimes malfunction, triggering the stress response in situations that are not genuinely dangerous [10, 12]. It's like a smoke alarm going off when you burn toast, the response out of proportion to the actual threat. This overreaction can lead to a variety of anxiety symptoms, such as:

-

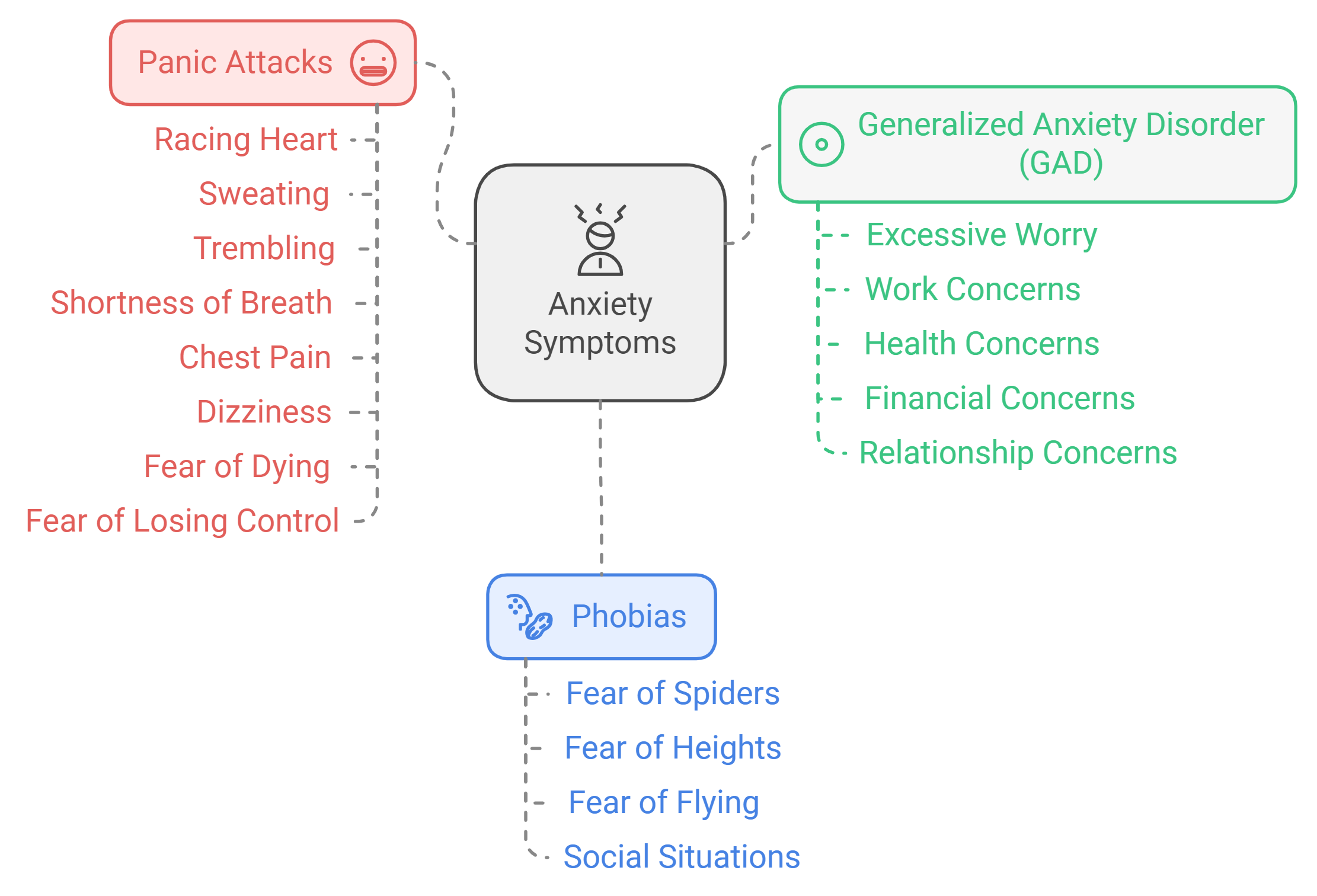

Panic Attacks: A panic attack is a sudden surge of intense fear or discomfort that peaks within minutes. It is characterized by physical symptoms such as a racing heart, sweating, trembling, shortness of breath, chest pain, dizziness, and a fear of dying or losing control [13]. Panic attacks can be terrifying, often leaving individuals feeling as though they are having a heart attack or going crazy.

-

Phobias: A phobia is an irrational and intense fear of a specific object or situation. Common phobias include fears of spiders, heights, flying, and social situations [14]. Phobias can be highly debilitating, leading individuals to avoid specific situations or objects, even if those situations or objects pose no real threat.

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): GAD is characterized by excessive and persistent worry about a variety of things, such as work, health, finances, and relationships [13, 15]. Individuals with GAD often find it difficult to control their worry, leading to significant distress and impairment in their daily lives.

A Tangled Web: The Interplay of Cortex and Amygdala

Anxiety is rarely a simple case of "thinking vs. feeling." In many cases, it involves a complex interplay between the cortex and the amygdala [2, 16]. The two pathways, like intertwined threads, work together to create the tapestry of our experience.

Imagine this interplay as a tennis match between the cortex and the amygdala. The cortex, with its ability to interpret and predict, might serve up a thought like, "What if I fail this presentation?" The amygdala, ever vigilant, volleys back with a surge of physical anxiety symptoms, such as a racing heart and sweaty palms. The cortex then returns the serve, interpreting these physical sensations as further evidence of danger, "See, I told you something was wrong!" This back-and-forth exchange can continue for some time, the anxiety escalating with each volley until it feels overwhelming.

Chemical Messengers: Understanding the Role of Neurotransmitters

While the cortex and amygdala provide the stage for anxiety, neurotransmitters play the role of stagehands, working behind the scenes to facilitate communication between neurons. These chemical messengers are essential for regulating mood, sleep, appetite, and the stress response [this information is not from the provided sources and may require independent verification]. Imbalances in neurotransmitter activity are implicated in a wide range of mental health conditions, including anxiety disorders.

Several key neurotransmitters are involved in anxiety:

-

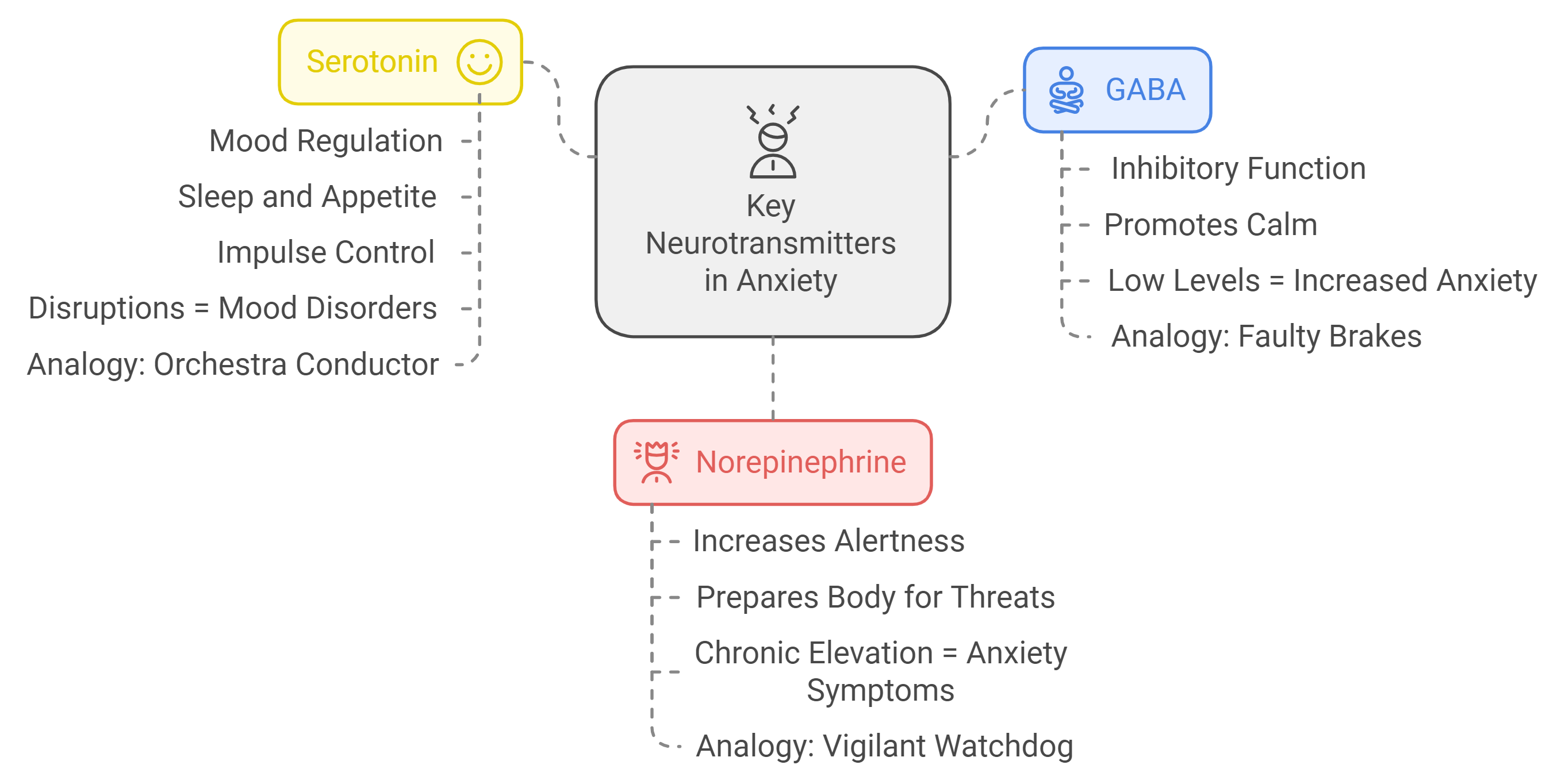

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA): GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that acts like a braking system in the brain, slowing down neuronal activity and promoting a sense of calm [this information is not from the provided sources and may require independent verification]. Low levels of GABA are associated with increased anxiety [this information is not from the provided sources and may require independent verification]. It's like having a car with faulty brakes; the slightest touch of the accelerator sends it careening out of control.

-

Serotonin: Often referred to as the "happy hormone," serotonin plays a crucial role in mood regulation, sleep, appetite, and impulse control [this information is not from the provided sources and may require independent verification]. Disruptions in serotonin signalling are linked to anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders [this information is not from the provided sources and may require independent verification]. Think of serotonin as a conductor in an orchestra, ensuring that all the instruments are playing in harmony. When serotonin levels are out of balance, the music becomes discordant, leading to emotional distress.

-

Norepinephrine: Norepinephrine is a neurotransmitter and hormone involved in the fight-or-flight response. It increases alertness, heart rate, and blood pressure, preparing the body to respond to threats [this information is not from the provided sources and may require independent verification]. When norepinephrine levels are chronically elevated, it can contribute to anxiety symptoms such as restlessness, racing thoughts, and difficulty sleeping [this information is not from the provided sources and may require independent verification]. Imagine norepinephrine as a vigilant watchdog, always on alert for potential danger. While this vigilance is essential for survival, it can become problematic when the watchdog barks at every passing car.

Rewiring the Anxious Brain: Strategies for Calming the Storm

Understanding the neuroscience of anxiety is not about accepting defeat, but about gaining empowerment. By understanding how anxiety manifests in the brain, we can begin to develop targeted and effective coping strategies.

Here are some evidence-based strategies grounded in neuroscience:

-

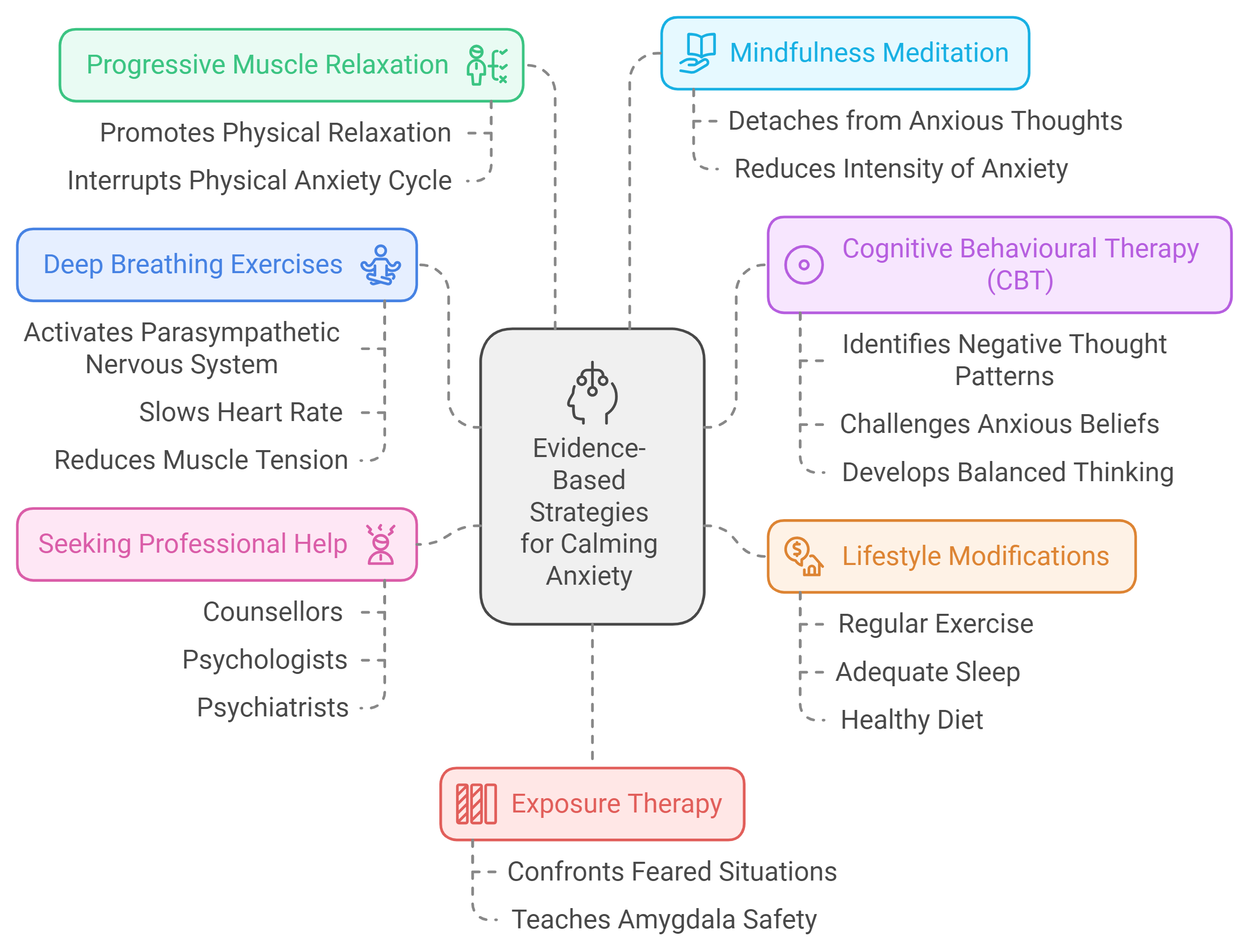

Deep Breathing Exercises: Deep, slow breathing techniques, such as diaphragmatic breathing, are like hitting the reset button on the stress response [7, 17, 18]. By activating the parasympathetic nervous system, the branch of the autonomic nervous system responsible for relaxation, deep breathing helps slow down the heart rate, lower blood pressure, and reduce muscle tension [7, 17, 18].

-

Progressive Muscle Relaxation: This technique involves systematically tensing and relaxing different muscle groups, promoting a deep sense of physical relaxation [7, 8, 17, 18]. By becoming aware of muscle tension and practicing relaxation, individuals can interrupt the cycle of physical anxiety symptoms and promote a sense of calm.

-

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): CBT is a type of therapy that helps identify and challenge negative thought patterns that contribute to anxiety [19-30]. It's like learning to become a detective of our thoughts, examining the evidence for and against our anxious beliefs, and developing more balanced and realistic thinking patterns.

-

Mindfulness Meditation: Mindfulness involves paying attention to the present moment without judgment [9, 24, 30, 31]. By cultivating a non-reactive awareness of our thoughts, feelings, and sensations, mindfulness helps us detach from anxious thoughts, reducing their intensity and impact [9, 24, 30, 31].

-

Exposure Therapy: Exposure therapy is a powerful technique for overcoming phobias and other anxiety disorders [17, 24, 32]. It involves gradually confronting feared situations in a safe and controlled manner, allowing the amygdala to learn that the feared stimulus is not truly dangerous [17, 24, 32]. It's like dipping our toes into a cold pool gradually, rather than jumping in all at once. By slowly acclimating ourselves to the feared situation, we can reduce the intensity of our anxiety response.

-

Lifestyle Modifications: Our physical and mental health are intricately intertwined. Exercise, adequate sleep, and a healthy diet are not just good for our bodies, they also have a profound impact on our brains [7, 33-36]. Regular exercise releases endorphins, natural mood-boosters that can alleviate anxiety and improve mood [7, 33-35]. Adequate sleep allows the brain to rest and restore itself, essential for emotional regulation and cognitive function [7, 33-35].

-

Seeking Professional Help: If anxiety is severe, persistent, or significantly interfering with daily life, seeking professional help is a crucial step [24, 37]. Counsellors, psychologists, and psychiatrists can provide evidence-based therapies, such as CBT, mindfulness-based interventions, and medication management if needed [24, 37, 38].

Conclusion

Anxiety is a multifaceted experience with deep roots in the intricate workings of our brains. By understanding the neuroscience behind anxiety, we can begin to reclaim our power, develop effective coping strategies, and live fuller, more meaningful lives.

Remember, seeking support is a sign of strength, not weakness. You are not alone on this journey, and with the right tools and support, you can navigate the challenges of anxiety and cultivate lasting peace of mind.