Describing Anxiety: Its Impact on the Brain, Behaviour, Thoughts, and Emotions

Oct 14, 2024

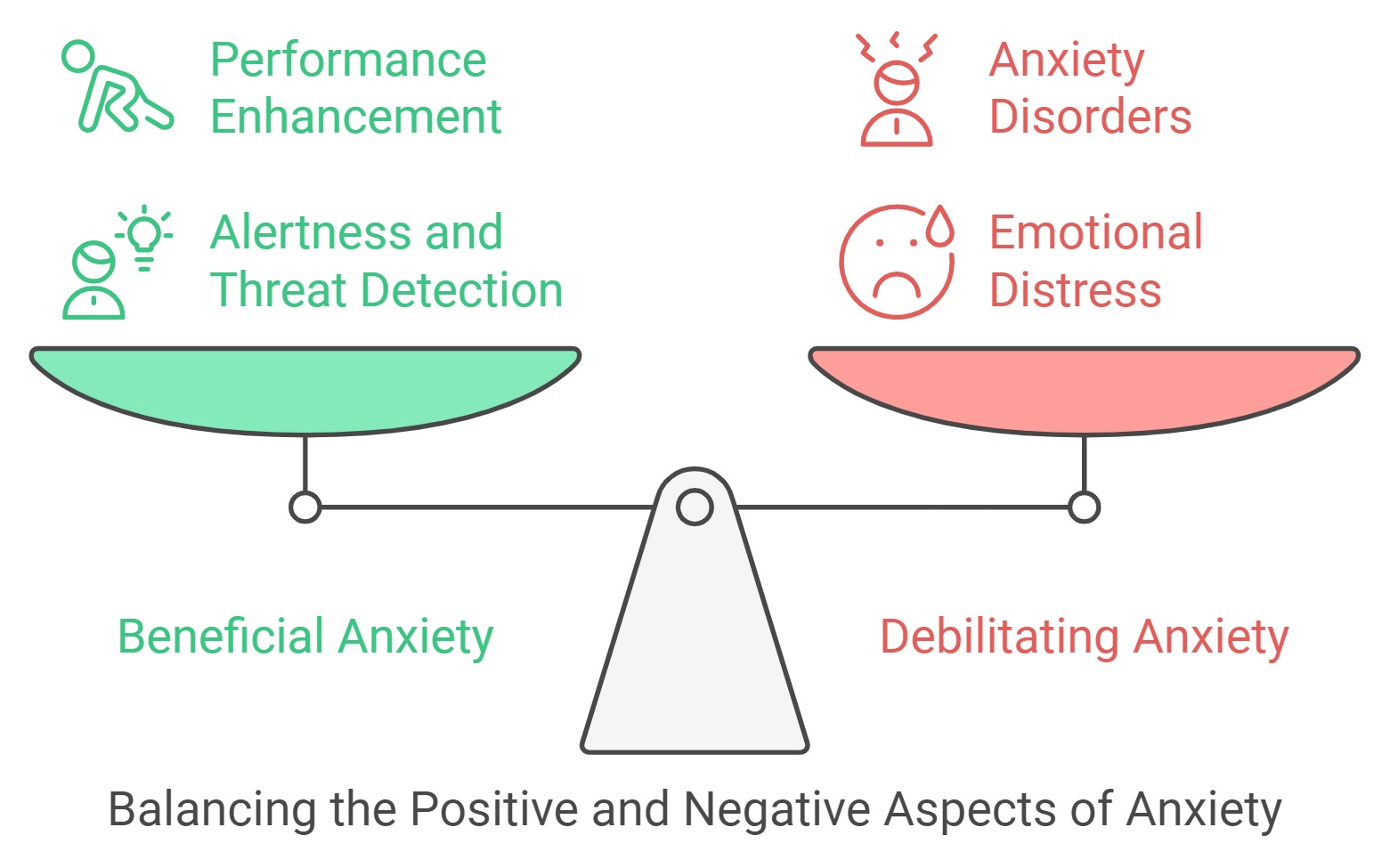

Anxiety is a familiar emotion that everyone experiences [1-6]. It's a natural human state and a vital part of life [2, 3]. In appropriate amounts, anxiety can be helpful, alerting individuals to potential threats, allowing for evaluation and response, helping with performance, and stimulating creativity and action [2, 3, 7]. However, when anxiety persists, it can become debilitating, leading to emotional distress, illness, and anxiety disorders such as panic attacks, phobias, and obsessive behaviours [2-4, 8].

The Neuroscience of Anxiety

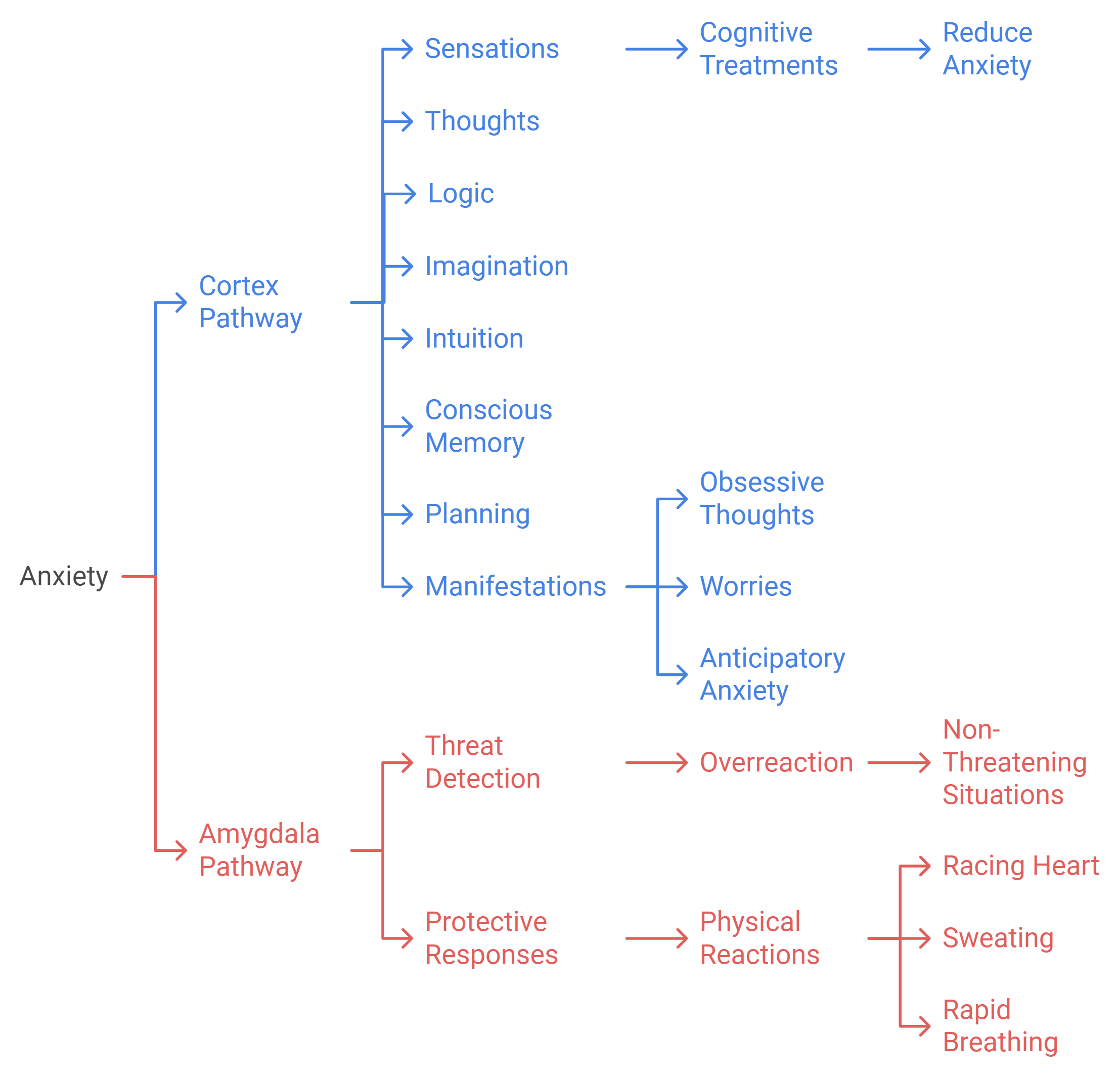

The brain plays a crucial role in the experience of anxiety. Recent research in neuroscience has illuminated how the brain creates anxiety, specifically through two neural pathways: the cortex pathway and the amygdala pathway [9-11].

-

The cortex pathway involves sensations, thoughts, logic, imagination, intuition, conscious memory, and planning [12]. This pathway is often targeted in anxiety treatment using cognitive approaches that modify thoughts to reduce worry [13]. Cortex-based anxiety can manifest as obsessive thoughts, worries, and anticipatory anxiety, even in the absence of real danger [14].

-

The amygdala pathway is responsible for detecting threats and initiating protective responses [9]. The amygdala, a small almond-shaped structure deep within the brain, acts as a protector, constantly vigilant for potential harm [15]. However, it can overreact, creating a fear response in non-threatening situations [15]. Amygdala-based anxiety is characterised by instant physical reactions such as a racing heart, sweating, and rapid breathing [15].

Both pathways are involved in the creation of anxiety, although some types of anxiety are more associated with one pathway than the other [10]. Understanding the origin of anxiety, whether cortex-based, amygdala-based, or a combination of both, is crucial for determining the most effective strategies for managing it [16, 17].

Behavioural Manifestations of Anxiety

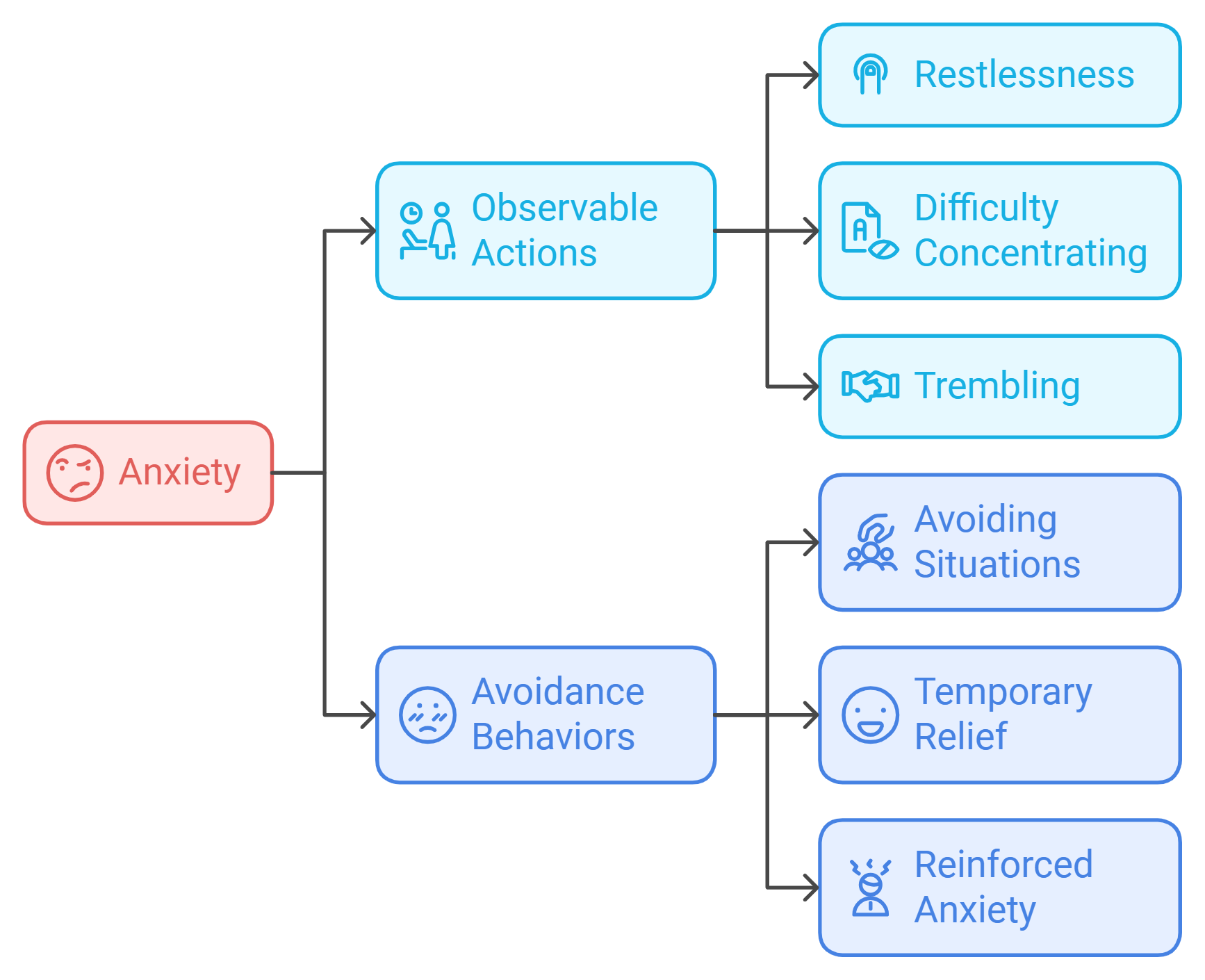

Anxiety significantly impacts behaviour, leading to both observable actions and avoidance behaviours:

-

Observable actions can include:

-

Restlessness and an inability to relax [18]

-

Finding it difficult to concentrate or experiencing mind blanks [18, 19]

-

A shaky voice and trembling or shaking [18]

-

Avoidance behaviours are common coping mechanisms for anxiety. These are actions people take to prevent or reduce anxiety by staying away from situations or triggers that provoke anxiety [20]. For example, an individual with social anxiety might avoid public speaking or social gatherings. While avoidance provides temporary relief, it reinforces anxiety in the long run, preventing individuals from learning that the feared situation is manageable [20].

It's important to note that the specific behaviours exhibited can vary greatly depending on the type and severity of anxiety, as well as individual differences.

The Cognitive Dimension of Anxiety

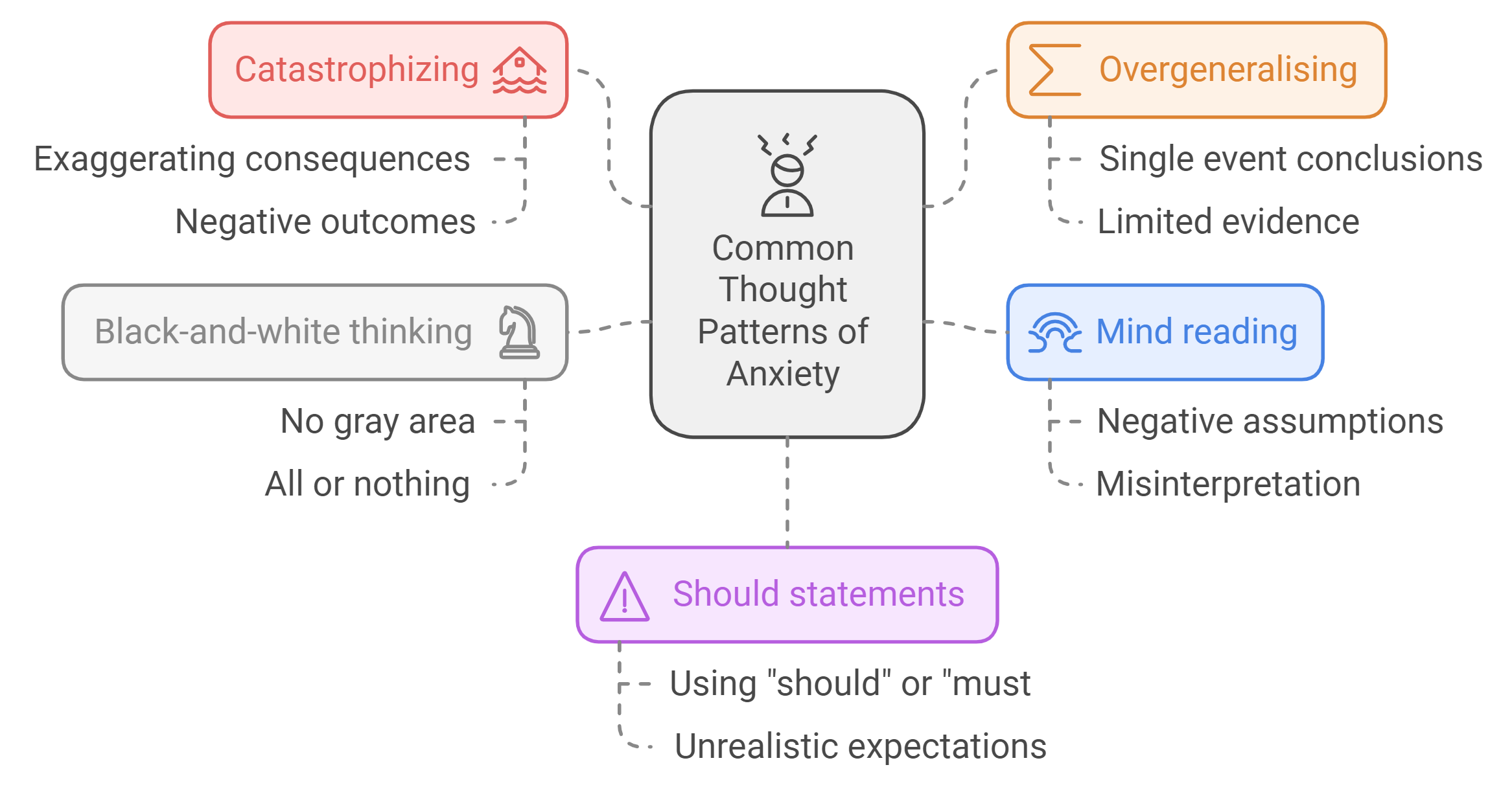

Anxiety profoundly affects thoughts, leading to negative thought patterns, worries, and cognitive distortions.

Here are some common thought patterns associated with anxiety:

-

Catastrophizing: Imagining worst-case scenarios and exaggerating the potential negative consequences of situations [21].

-

Overgeneralising: Drawing sweeping conclusions based on a single event or limited evidence [22].

-

Mind reading: Assuming you know what others are thinking, often negatively [18].

-

Black-and-white thinking: Viewing situations in extreme terms, with no middle ground [23].

-

Should statements: Placing unrealistic demands on yourself or others using "should," "must," or "ought to" statements [23].

These negative thought patterns contribute to the vicious cycle of anxiety, where anxious thoughts trigger physical symptoms, which further fuel anxious thoughts [24]. Identifying and challenging these cognitive distortions is a key component of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), a widely used and effective treatment for anxiety disorders [25-27].

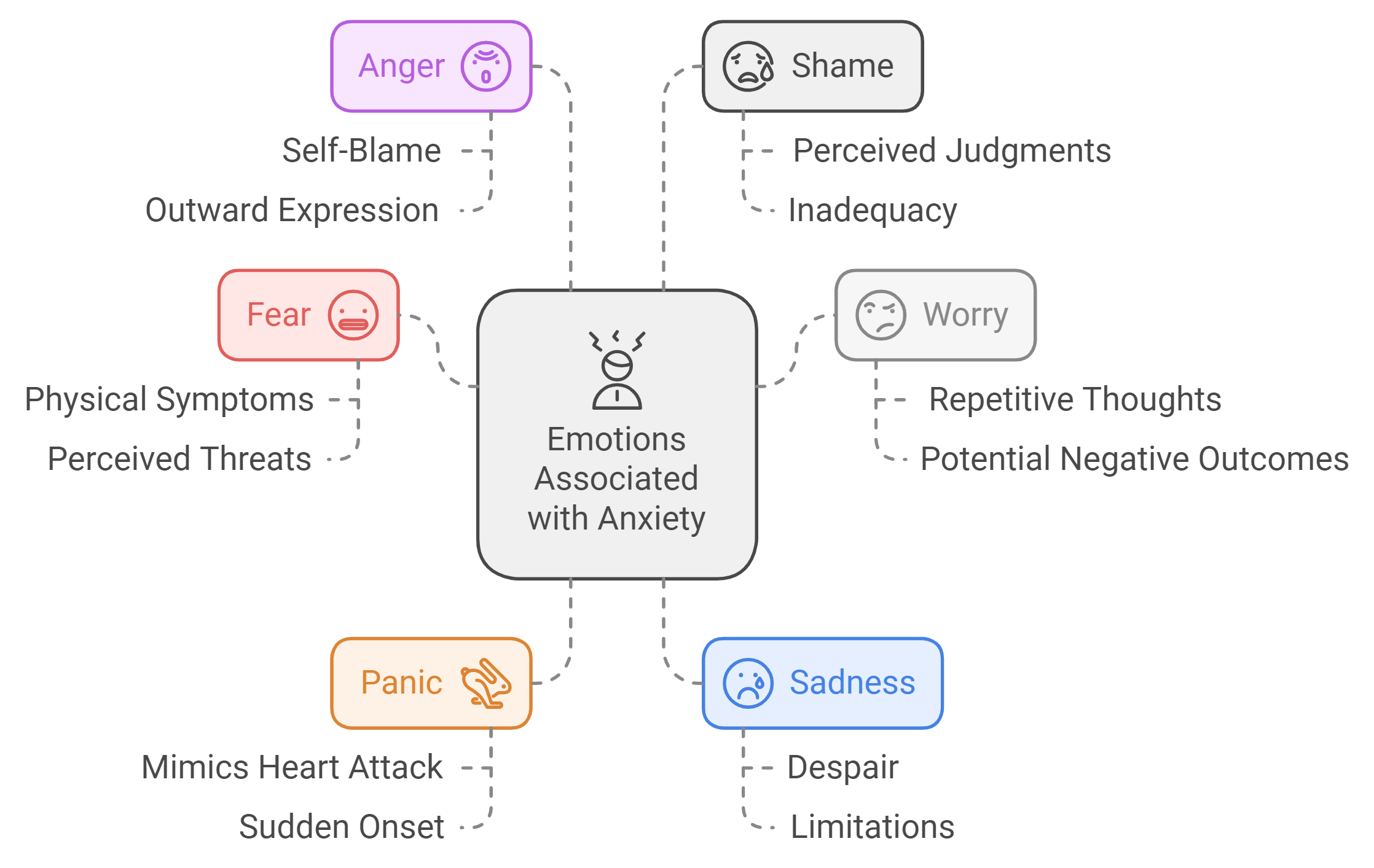

The Emotional Landscape of Anxiety

Anxiety is often accompanied by a range of intense and unpleasant emotions:

-

Fear: A basic human emotion triggered by perceived threats, often accompanied by physical symptoms such as a racing heart and sweating [28].

-

Worry: A state of mental unease and apprehension about potential negative outcomes, characterised by repetitive thoughts and images [29].

-

Panic: A sudden and overwhelming surge of fear and anxiety, often accompanied by physical symptoms that can mimic a heart attack [8].

-

Sadness: A feeling of unhappiness and despair that can arise from the limitations and distress caused by anxiety [30].

-

Anger: A natural response to feeling threatened or frustrated, which can be directed inward (self-blame) or outward (towards others) [31].

-

Shame: A painful emotion associated with feeling flawed or inadequate, often stemming from perceived judgments by others [30].

These emotions contribute to the overall distress and impairment experienced by individuals with anxiety disorders. Learning to manage and regulate these emotions is crucial for recovery.

Scenarios and Stories

Here are a few scenarios and stories that illustrate how anxiety can affect an individual's thoughts, feelings, and behaviours:

-

Scenario 1: Public Speaking Anxiety

-

Imagine a university student, Sarah, who has to present her research project to the class. Sarah experiences significant anxiety about public speaking. Her thoughts race: "What if I forget everything? What if they think I'm stupid? What if I make a fool of myself?" These thoughts trigger physical symptoms such as a racing heart, sweating, and trembling hands. As a result, Sarah avoids eye contact, speaks quickly and in a shaky voice, and rushes through her presentation. The experience reinforces her fear of public speaking, and she vows to avoid similar situations in the future.

-

Scenario 2: Social Anxiety

-

Mark is invited to a party with his colleagues. He wants to go, but he feels overwhelmed with anxiety at the thought of socialising with people he doesn't know well. He worries about saying the wrong thing, being judged, and feeling awkward. Mark decides to decline the invitation, making an excuse about being busy. This avoidance behaviour, while providing temporary relief, reinforces his social anxiety and prevents him from building social confidence.

-

Story from the Sources:

-

The source material provides a personal account from 'Ian', who struggled with anxiety for many years. He describes how anxiety took root in his life, causing him to feel ashamed and embarrassed [32]. However, through understanding his anxiety, developing coping techniques, and sharing his experiences with others, Ian was able to manage his anxiety and even use it in a positive way by helping others [32]. This story highlights the importance of seeking support, learning coping strategies, and challenging the stigma associated with anxiety.

Conclusion

Anxiety is a multifaceted emotion that can significantly impact an individual's brain, behaviour, thoughts, and emotions. Understanding the neuroscience of anxiety, recognising its behavioural manifestations, identifying and challenging negative thought patterns, and learning to manage the emotional landscape of anxiety are crucial steps towards recovery. By seeking professional help, developing coping mechanisms, and sharing experiences with others, individuals can learn to manage anxiety and live fulfilling lives.